Information

Author: Jenny Volstorf

Version: B | 1.2Published: 2023-07-26

link corrections

1 Summary

2 General

- Escapes: rear only in environments where it naturally occurs D1 and prevent escapes. Else, escapees from fish farms have negative or at most unpredictable influences on the local ecosystem D2. Prepare for sexual maturity (and thus spawning) from 6 months or 21 cm on D3 and take measures against spawning into the wild.

Note of dissent:

The reviewer does not feel comfortable with this recommendation which to her opinion is ethically and not scientifically based.

The author and the editor adhere to the recommendation above because negative impacts on the ecosystem impair the wild animals living there, and animal welfare is the core issue of FishEthoBase.

3 Designing the (artificial) habitat

3.1 Substrate and/or shelter

- Substrate:

- Shelter or cover:

- Cover: in the wild, might take cover from overhead in sand during the night D6. For the most natural solution, provide enough sand to allow for burrowing; alternatively, provide artificial shelters inside the system or outside. Avoid complete cover in respect for the diurnal rhythm A2.

- Vegetation: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Shelters: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

3.2 Photoperiod

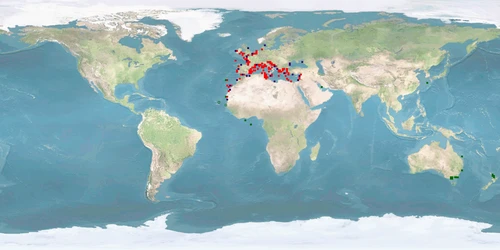

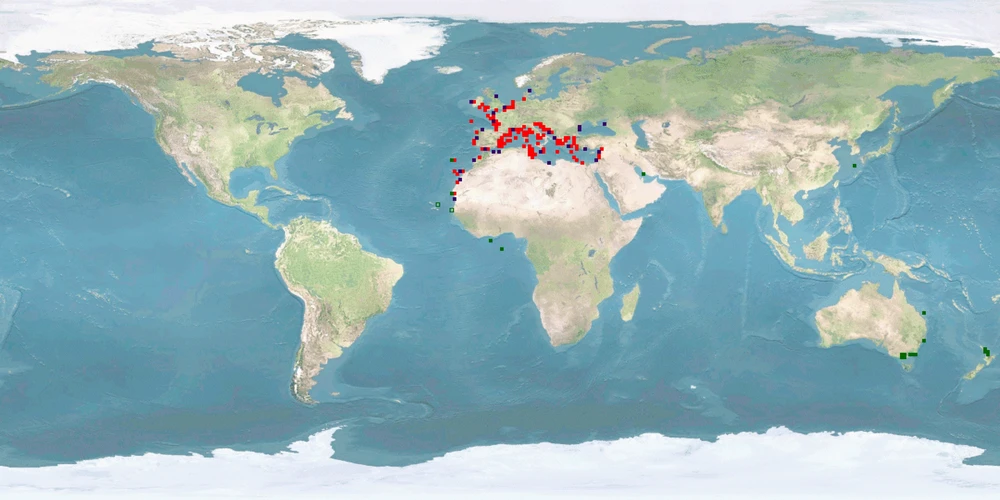

- Photoperiod: given the distribution D1 D7, natural photoperiod is 8-16 hours, depending on the season. Provide access to natural (or at least simulated) photoperiod and daylight. Some evidence to best keep larvae in dark surrounding for first 60+ hours until mouth opening, afterwards under 24 hours photoperiod for best survival D8. Further research needed.

- Light intensity: for better growth in juveniles, provide 200 lux than 80 lux D9. Further research needed.

- Light colour: avoid red light, as it decreases growth and might induce stress D10. Further research needed.

- Resting period: respect the diurnal rhythm of Gilthead seabream and its resting period at night or in the dark D8.

3.3 Water parameters

- Temperature: no clear temperature preference, probably best kept at 11-30 °C D11 without large fluctuations, as this impairs growth D12, larvae at 16-22 °C D13; adjust temperature when you notice avoidance behaviour D14 D15. Implemented in aquaculture, temperatures >22 °C demand excellent oxygen levels and a fine-tuned flow-through system to prevent bacterial load.

- Water velocity: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Oxygen: maintain oxygen level that ensures welfare depending on temperature (→ Temperature) and stocking density (→ A3).

- Salinity: given the amphidromous migration type, natural salinity is at seawater level at hatching and oscillates between seawater level in winter and brackish water the rest of the year from fry to adult stage D16 D17. Keep fry at salinities of 18-28‰ for best growth D18. Further research needed. Salinity tolerance increases with age D19. Further research needed.

- pH: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Turbidity: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

3.4 Swimming space (distance, depth)

- Distance: in the wild, some hints for various lagoon use, some hints for site fidelity D20. Provide enough space, bearing in mind the planned stocking density A3.

- Depth:

- Depth range: in the wild, found at 0-30 m, seldomly up to 150 m D21. Provide at least 3-5 m, ideally up to 30 m, bearing in mind the planned stocking density A3. Individuals should be able to choose swimming depths according to life stage and status D21 D22 D23.

- Flight: provide enough depth for the flight response to light D21; depth use does not seem to be limited D21.

- Temperature layers: in habitats with water layers with different temperatures, prepare for individuals migrating to layers with preferred temperatures D11, and avoid crowding in these layers by providing enough space.

4 Feeding

- Alternative species: mainly carnivorous D24, trophic level 3.7 D25. If you have not yet established a Gilthead seabream farm, you might consider to opt for a species that can be fed without or with much less fish meal and fish oil in order not to contribute to overfishing by your business D26.

- Protein substitution: if you run a Gilthead seabream farm already, try to substitute protein feed components that have so far been derived from wild fish catch, while taking care to provide your fishes with a species-appropriate feed D24:

- Invite a feed mill and other fish farmers in your country to jointly establish a recycling syndicate that converts the remainders and the offcuts of fish processing into fish meal and fish oil, separating the production line corresponding to the species of origin in order to avoid cannibalism →fair-fish farm directives (point 6).

- Inform yourself about commercially tested substitutes for fish meal and fish oil, like insect or worm meal or soy, with an appropriate amino and fatty acid spectrum.

Note of dissent:

The reviewer disagrees with this recommendation which to her opinion has to do with overfishing and ethics but not with animal welfare.

The author and the editor adhere to the recommendation above because overfishing impairs the marine food chain and consequently the living of marine animals, thus animal welfare, not to speak of about 450,000,000,000-1,000,000,000,000 fishes caught for feed annually.

- Feed delivery:

- Feeding frequency and time, feed delivery, self-feeders: in the wild, benthic feeder D27, mostly diurnal D8. Refrain from feeding during night time in respect for Gilthead seabream's natural resting period. Keeping to a feeding schedule decreases stress but increases locomotion due to food-anticipatory behaviour D28. Further research needed. Feed slowly to avoid waste and a bad feed conversion ratio D29. Note decreased feeding at temperatures <16 °C and >30 °C D14 and reduce the amount of food offered accordingly. Alternatively, install a self-feeder and make sure all Gilthead seabream adapt to it.

- Food competition: make sure to provide sufficient feed from ca 4-6 days after hatching on D30. In small groups, size-grade juveniles, because food competition results in variable growth rates D31. Alternatively, provide a ration of ca 3% body weight to decrease food competition and waste and increase growth D32. Further research needed.

- Particle size: fry naturally feed on live prey but accept microencapsulated food as well D24. With microencapsulated food, provide smaller size compared to live food, and soft rather than hard shell D24. Adding visual and olfactory stimuli of live food increases ingestion D33 D34.

- Feed enrichment: to improve stress tolerance, enrich feed for fry with arachidonic acid or prebiotic Pdp11, and ensure vitamin E D35.

5 Growth

- Maturity: in the wild, matures in the first or second year D3. Although manipulating time of maturity is possible D36, refrain from it, as we have not found studies reporting possible long-term effects on welfare →fair-fish database's understanding of fish welfare.

- Manipulating sex: even if manipulating sex were possible, refrain from it, as we have not found studies reporting possible long-term effects on welfare →fair-fish database's understanding of fish welfare.

- Sex ratio: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Size-grading: when in small groups, better size-grade juveniles, otherwise they aggressively establish a social hierarchy D37 which increases stress D22 D23 and influences growth D31. In larger groups, comparable aggression in single-size and mixed-size populations D38, so size-grading does not seem beneficial.

- Other effects on growth:

- Music: for better growth, play music D39. Further research needed.

- Deformities and malformations: as hatchery-reared larvae display a varying range of skeletal deformities and morphological malformations D40 with unknown cause D41 and because using wild-caught larvae is not ecologically sustainable, there is no recommendable rearing method at the moment.

Note of dissent:

The reviewer disagrees, because she regards deformities, malformations, and the resulting loss of larvae as not caused by the farming procedures and as part of the business plan. Also, catching wild larvae, for her, is primarily a sustainability issue and not related to fish welfare.

The author and the editor hold on to the statement, because for them, continuing to rear Sparus aurata under the premise of deformities and malformations is ethically questionable. Alternatively catching wild larvae is as much a sustainability as a welfare issue for them.- For growth and...

...light intensity →A2,

...light colour →A2,

...water temperature →A4,

...salinity →A4,

...food competition →A5,

...stimuli of live food →A5.

6 Reproduction

- Nest building: sea spawner D42.

- Courtship, mating: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Spawning conditions: respect natural spawning season in autumn to spring in seawater D43. No ethology-based recommendation definable on specific temperature, salinity, water velocity, depth, and spawning sequence. Since growth is heritable, select breeding individuals by weight and length D44. For less fluctuation in number of eggs and more fertilisation by the males, keep females grouped (not solitary) in small mixed-sex groups D45. Further research needed. Do not change composition of the broodstock shortly before spawning to prevent a decrease in fecundity of the females D45.

- Fecundity: 4,100-80,000 eggs daily per female for 4-100 days D46. For highest fecundity, collect eggs during the first full moon of the month D47. Although manipulating fecundity is possible D48, refrain from it, as we have not found studies reporting possible long-term effects on welfare → fair-fish database's understanding of fish welfare.

7 Stocking density

- Maximum: the businessplan should be calculated on the basis of a maximum stocking density that will never exceed the tolerable maximum with regard to fish welfare.

- Stocking:

- Restriction:

- Habitat structuring: consider loss of space due to structures inside and outside the system A6 and calculate density accordingly.

- Environmental conditions: in the wild, displays a large variability in preferences for substrate D51 D4, water temperature D11, and depth D21. Consider increased density at places with preferential conditions A6 A4 A7 and calculate density accordingly.

- Aggregation: smaller individuals build schools D49. Consider increased density at places due to formation of schools and calculate density accordingly.

- Aggression: choose density given displayed aggression. Further research needed. Aggression may entail displays, attacks, circles, chases, nips D38.

- Territoriality: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Interaction: as show the above influence factors, stocking density is only one part of a complex interaction of factors to affect welfare. It should never be considered isolatedly.

8 Occupation

- Food search: provide sand, rocks, or gravel and seagrass so that individuals may search for food D4 D27.

- Challenges: if after decreasing stress A8 and providing everything welfare assuring, you still notice stereotypical behaviour, vacuum activities, sadness, then provide mental challenges, diversion, variety, and check reactions.

9 Handling, slaughter

9.1 Handling

- Stress coping styles: individuals differ in their ability to cope with stress D52, so assume the smallest common denominator during stressful situations and handle with care and high efficiency.

- Stress measurement:

- Stress reduction:

- Noise: avoid sounds of 0.1-1 kHz, as it causes stress D55. If unavoidable, play offshore sounds to reduce stress D55. Further research needed.

- Directing individuals: to direct individuals in the habitat (e.g., for cleaning purposes), use acoustic stimuli D56.

- Cage submergence: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Pain treatment: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Handling: handle as carefully as possible, as it might increase aggression D57 and causes stress D58.

- Confinement: avoid confinement, as it causes stress D58.

Note of dissent:

The reviewer does not see how confinement can be avoided and would recommend to keep it (and any other stressful event) to a minimum.

The author does not feel comfortable to recommend the latter without being able to give a definition what “minimum” means.- Crowding: avoid crowding, as it causes stress D59.

- Transport: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- Disturbance: no ethology-based recommendation definable so far.

- For stress reduction and...

...substrate colour →A6,

...light colour →A2,

...water temperature →A4,

...feed delivery →A5,

...feed enrichment →A5,

...size-grading →A9,

...stocking density →A3.

9.2 Slaughter

- Stunning rules: render individuals unconscious as fast as possible and make sure stunning worked and they cannot recover D60.

- Stunning methods: prefer percussive stunning, because it renders individuals unconscious fast if administered correctly and with sufficient force D61. Alternatively, use electrical stunning for at least 10 seconds with >200 mA D61. Further research needed for a specific protocol.

- Slaughter methods: bleed or gut individuals immediately after stunning, i.e. while unconscious.

10 Certification

- Certification: fair-fish international association warmly advises to follow one of the established certification schemes in aquaculture in order to improve the sustainability of aquafarming. Adhering to the principles of one of these schemes, however, does not result in animal welfare by itself, because all these schemes do not treat animal welfare as a core issue or as an issue at all. Therefore the FishEthoBase has been designed as a complement to any of the established certification schemes. May it help practitioners to improve the living of the animals they farm based on best scientific evidence at hand.

- To give you a short overview of the most established schemes, we present them below in descending order of their attention for animal welfare (which is not necessarily the order of their sustainability performance):

- The fair-fish farm directives are not present on the market, we cite them here as a benchmark. The directives address fish welfare directly by being committed to FishEthoBase: for each species, specific guidelines are to be developed mirroring the recommendations of FishEthoBase; species not yet described by FishEthoBase cannot be certified. In addition, the directives address a solution path for the problem of species-appropriate feeding without contributing to overfishing.

- The Naturland Standards for Organic Aquaculture (Version 06/2018) generally address animal welfare with words similar to the fair-fish approach: "The husbandry conditions must take the specific needs of each species into account as far as possible (…) and enable the animal to behave in a way natural to the species; this refers, in particular, to behavioural needs regarding movement, resting and feeding as well as social and reproduction habits. The husbandry systems shall be designed in this respect, e.g. with regard to stocking density, soil, shelter, shade and flow conditions".

In the details, however, the standards scarcely indicate tangible directives for Gilthead seabream, except for percids in general when cultured in marine net cages: no grow-out in artificial tanks, stocking density limited to 10 kg fish/m3 max. Live transportation is limited to 10 hours max, to 1 kg/8 L max, and to adequate provision of oxygen, with water exchange after six hours. - The GAA-BAP Finfish and Crustacean Farms Standard (Issue 2.4, May 2017) directly addresses animal welfare: "Producers shall demonstrate that all operations on farms are designed and operated with animal welfare in mind." Farms shall "provide well-designed facilities", "minimize stressful situations" and train staff "to provide appropriate levels of husbandry". Yet the standard does not provide tangible and detailed instructions for the practitioner, let alone species-specific directives.

In September 2017, GAA-BAP received a grant from the Open Philanthropy Project to develop best practices and proposed animal welfare standards for salmonids, tilapia, and channel catfish. Thus, fish welfare on GAA-BAP certified farms might become more tangible in the future, eventually also for Gilthead seabream at a later date. - The GlobalG.A.P. Aquaculture Standard (Version 4.0, March 2013) "sets criteria for legal compliance, for food safety, worker occupational health and safety, animal welfare, and environmental and ecological care". The inspection form includes criteria like "Is the farm management able to explain how they fulfil their legal obligations with respect to animal welfare?", "If brood fish are stripped, this should be done with the consideration of the animal's welfare." or "Is a risk assessment for animal welfare undertaken?" The scheme claims that 45 out of a total of 249 control points cover animal protection, yet it does not provide any tangible directives, let alone species-specific directives.

- The ASC Aquaculture Stewardship Council. The ASC standards address fish welfare only indirectly, as a function of a “minimum average growth rate" per day, a "maximum fish density at any time", and a "maximum average real percentage mortality". fair-fish sees animal welfare as an intrinsic value, not just as a result of optimising neighbouring values like health care and management procedures.

The ASC standard for Gilthead seabream (version 1.1, March 2019) does not specify threshold values for the above mentioned minima resp. maxima.

In November 2017, ASC received a grant from the Open Philanthropy Project to develop an evidence-based fish welfare standard that is applicable to all ASC-certified species. ASC intends to share its approach to fish welfare with all farms engaged with the ASC program and encourage adoption of it, which means that the fish welfare standard will function as a non-mandatory add-on to the ASC certification. - The Friend of the Sea (FOS) Standards for marine aquaculture of fish (revised November 2014) do not even address animal health or animal welfare issues.

In May 2017 however, FOS signed a Memory of Understanding with fair-fish international on developing fish welfare criteria for the FOS standard. In November 2017 fair-fish international association received a grant from the Open Philanthropy Project to assess the welfare of fish on FOS certified farms, develop farm-specific recommendations, and to develop animal welfare criteria for the FOS standard. Thus, fish welfare on FOS certified farms might become tangible in the future.

In the "Advice", we summarise findings from the literature regarding some basic criteria that are important to assure good welfare in aquaculture facilities: designing the (artificial) habitat, feeding, growth, reproduction, stocking density, occupation, handling/slaughter. The literature base comes from the "Dossier" (separate tab on top) where one may also find the respective references.

At first sight, the "Advice" might read as something resembling a farming manual, but we would like to stress that it's not meant like this. Yes, we do our best to give the insights from the literature with the aim of assuring good welfare in aquaculture. There are two reasons why the "Advice" is not a rearing manual:

- to set up or maintain an aquaculture facility, many more criteria are important to know and monitor. For example, we do not cover water parameters in detail

- our source for everything on this page is an – albeit vast – literature check. We did not consult with aquaculture experts or got hands-on knowledge ourselves. Some of the studies were done in the lab, though, and might need to be verified for the farming context.

In sum, our idea with the "Advice" is to summarise what the literature has to say about how to assure good welfare in aquaculture. Please also note that the "Advice" is a part of the database that we put on hold a few years ago to focus more on the WelfareChecks. Therefore, all of the 11 "Advices" (2013-2019) certainly need an update.

Probably, we updated the profile. Check the version number in the head of the page. For more information on the version, see the FAQ about this. Why do we update profiles? Not just do we want to include new research that has come out, but we are continuously developing the database itself. For example, we changed the structure of entries in criteria or we added explanations for scores in the WelfareCheck | farm. And we are always refining our scoring rules.

The centre of the Overview is an array of criteria covering basic features and behaviours of the species. Each of this information comes from our literature search on the species. If we researched a full Dossier on the species, probably all criteria in the Overview will be covered and thus filled. This was our way to go when we first set up the database.

Because Dossiers are time consuming to research, we switched to focusing on WelfareChecks. These are much shorter profiles covering just 10 criteria we deemed important when it comes to behaviour and welfare in aquaculture (and lately fisheries, too). Also, WelfareChecks contain the assessment of the welfare potential of a species which has become the main feature of the fair-fish database over time. Because WelfareChecks do not cover as many criteria as a Dossier, we don't have the information to fill all blanks in the Overview, as this information is "not investigated by us yet".

Our long-term goal is to go back to researching Dossiers for all species covered in the fair-fish database once we set up WelfareChecks for each of them. If you would like to support us financially with this, please get in touch at ffdb@fair-fish.net

See the question "What does "not investigated by us yet" mean?". In short, if we have not had a look in the literature - or in other words, if we have not investigated a criterion - we cannot know the data. If we have already checked the literature on a criterion and could not find anything, it is "no data found yet". You spotted a "no data found yet" where you know data exists? Get in touch with us at ffdb@fair-fish.net!

First up, you will find answers to questions for the specific page you are on. Scrolling down in the FAQ window, there are also answers to more general questions. Explore our website and the other sub pages and find there the answers to questions relevant for those pages.

In the fair-fish database, when you have chosen a species (either by searching in the search bar or in the species tree), the landing page is an Overview, introducing the most important information to know about the species that we have come across during our literatures search, including common names, images, distribution, habitat and growth characteristics, swimming aspects, reproduction, social behaviour but also handling details. To dive deeper, visit the Dossier where we collect all available ethological findings (and more) on the most important aspects during the life course, both biologically and concerning the habitat. In contrast to the Overview, we present the findings in more detail citing the scientific references.

Depending on whether the species is farmed or wild caught, you will be interested in different branches of the database.

Farm branch

Founded in 2013, the farm branch of the fair-fish database focuses on farmed aquatic species.

Catch branch

Founded in 2022, the catch branch of the fair-fish database focuses on wild-caught aquatic species.

The heart of the farm branch of the fair-fish database is the welfare assessment – or WelfareCheck | farm – resulting in the WelfareScore | farm for each species. The WelfareCheck | farm is a condensed assessment of the species' likelihood and potential for good welfare in aquaculture, based on welfare-related findings for 10 crucial criteria (home range, depth range, migration, reproduction, aggregation, aggression, substrate, stress, malformations, slaughter).

For those species with a Dossier, we conclude to-be-preferred farming conditions in the Advice | farm. They are not meant to be as detailed as a rearing manual but instead, challenge current farming standards and often take the form of what not to do.

In parallel to farm, the main element of the catch branch of the fair-fish database is the welfare assessment – or WelfareCheck | catch – with the WelfareScore | catch for each species caught with a specific catching method. The WelfareCheck | catch, too, is a condensed assessment of the species' likelihood and potential for good welfare – or better yet avoidance of decrease of good welfare – this time in fisheries. We base this on findings on welfare hazards in 10 steps along the catching process (prospection, setting, catching, emersion, release from gear, bycatch avoidance, sorting, discarding, storing, slaughter).

In contrast to the farm profiles, in the catch branch we assess the welfare separately for each method that the focus species is caught with. In the case of a species exclusively caught with one method, there will be one WelfareCheck, whereas in other species, there will be as many WelfareChecks as there are methods to catch the species with.

Summarising our findings of all WelfareChecks | catch for one species in Advice | catch, we conclude which catching method is the least welfare threatening for this species and which changes to the gear or the catching process will potentially result in improvements of welfare.

Welfare of aquatic species is at the heart of the fair-fish database. In our definition of welfare, we follow Broom (1986): “The welfare of an individual is its state as regards its attempts to cope with its environment.” Thus, welfare may be perceived as a continuum on which an individual rates “good” or “poor” or everything in between.

We pursue what could be called a combination of not only a) valuing the freedom from injuries and stress (function-based approach) but b) supporting attempts to provide rewarding experiences and cognitive challenges (feelings-based approach) as well as c) arguing for enclosures that mimic the wild habitat as best as possible and allow for natural behaviour (nature-based approach).

Try mousing over the element you are interested in - oftentimes you will find explanations this way. If not, there will be FAQ on many of the sub-pages with answers to questions that apply to the respective sub-page. If your question is not among those, contact us at ffdb@fair-fish.net.

It's right here! We decided to re-name it to fair-fish database for several reasons. The database has grown beyond dealing purely with ethology, more towards welfare in general – and so much more. Also, the partners fair-fish and FishEthoGroup decided to re-organise their partnership. While maintaining our friendship, we also desire for greater independence. So, the name "fair-fish database" establishes it as a fair-fish endeavour.