Information

Authors: Jenny Volstorf, João L. Saraiva

Version: C | 2.2Published: 2024-12-31

- minor editorial changes plus new side note "Commercial relevance"

WelfareScore | farm

The score card gives our welfare assessments for aquatic species in 10 criteria.

For each criterion, we score the probability to experience good welfare under minimal farming conditions ("Likelihood") and under high-standard farming conditions ("Potential") representing the worst and best case scenario. The third dimension scores how certain we are of our assessments based on the number and quality of sources we found ("Certainty").

The WelfareScore sums just the "High" scores in each dimension. Although good welfare ("High") seems not possible in some criteria, there could be at least a potential improvement from low to medium welfare (indicated by ➚ and the number of criteria).

- Li = Likelihood that the individuals of the species experience good welfare under minimal farming conditions

- Po = Potential of the individuals of the species to experience good welfare under high-standard farming conditions

➚ = potential improvements not reaching "High" - Ce = Certainty of our findings in Likelihood and Potential

WelfareScore = Sum of criteria scoring "High" (max. 10 per dimension)

General remarks

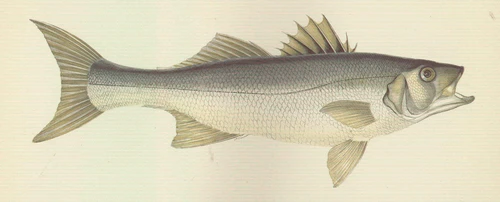

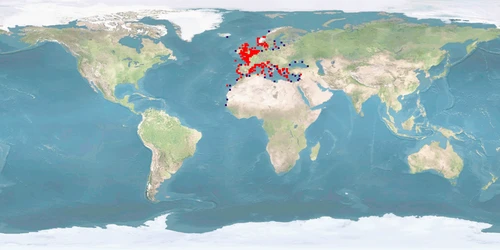

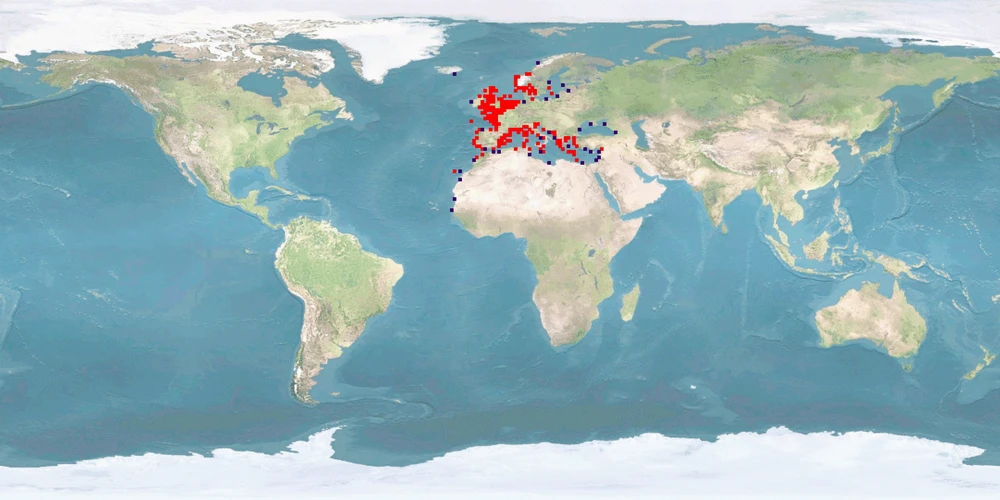

Dicentrarchus labrax, a moronid from the Eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, is a valuable species for aquaculture, dominating the Mediterranean marine finish culture together with Sparus aurata. Many aspects of its biology, however, are not taken into consideration in farming conditions, especially in intensive culture which represents the most frequent farming system using sea cages. Raceways, tanks, and ponds are also used, but to a lesser degree. Despite recent advances in nutrition, there is still dependence on unsustainable feed sources such as fish meal and oil. Many behavioural aspects are yet to be fully understood, namely on reproduction, where courtship processes are unknown and spawning has largely to be artificially induced. Spatial needs are also an issue, since farming conditions are generally too restrictive of natural movement. This species is known to be highly sensitive to stressors at all life stages, although good practices can greatly reduce stress effects. A proper culture system, providing shelter and substrate, reducing densities based on natural numbers and increasing space are measures that should contribute to better farming practices.

1 Home range

Many species traverse in a limited horizontal space (even if just for a certain period of time per year); the home range may be described as a species' understanding of its environment (i.e., its cognitive map) for the most important resources it needs access to.

What is the probability of providing the species' whole home range in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions, as the range in captivity at least overlaps with the range in the wild. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

2 Depth range

Given the availability of resources (food, shelter) or the need to avoid predators, species spend their time within a certain depth range.

What is the probability of providing the species' whole depth range in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions, as the range in captivity at least overlaps with the range in the wild. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

3 Migration

Some species undergo seasonal changes of environments for different purposes (feeding, spawning, etc.), and to move there, they migrate for more or less extensive distances.

What is the probability of providing farming conditions that are compatible with the migrating or habitat-changing behaviour of the species?

It is low for minimal and high-standard farming conditions, as the species undertakes extensive migrations, and we cannot be sure that providing each age class with their respective environmental conditions will satisfy their urge to migrate or whether they need to experience the transition. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

4 Reproduction

A species reproduces at a certain age, season, and sex ratio and possibly involving courtship rituals.

What is the probability of the species reproducing naturally in captivity without manipulation of these circumstances?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is high for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

5 Aggregation

Species differ in the way they co-exist with conspecifics or other species from being solitary to aggregating unstructured, casually roaming in shoals or closely coordinating in schools of varying densities.

What is the probability of providing farming conditions that are compatible with the aggregation behaviour of the species?

It is low for minimal farming conditions, as – even in the absence of densities in the wild – we may conclude from laboratory studies that densities in raceways and tanks are potentially stress inducing. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions, as lower stress at stocking densities in cages and ponds need to be verified for the farming context. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

6 Aggression

There is a range of adverse reactions in species, spanning from being relatively indifferent towards others to defending valuable resources (e.g., food, territory, mates) to actively attacking opponents.

What is the probability of the species being non-aggressive and non-territorial in captivity?

It is unclear for minimal farming conditions. It is high for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

7 Substrate

Depending on where in the water column the species lives, it differs in interacting with or relying on various substrates for feeding or covering purposes (e.g., plants, rocks and stones, sand and mud, turbidity).

What is the probability of providing the species' substrate and shelter needs in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions, as cages without substrate prevail. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions, as innovations for enrichment need to be verified for the farming context. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

8 Stress

Farming involves subjecting the species to diverse procedures (e.g., handling, air exposure, short-term confinement, short-term crowding, transport), sudden parameter changes or repeated disturbances (e.g., husbandry, size-grading).

What is the probability of the species not being stressed?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions, as some stressors result from conditions that may be changed. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

9 Malformations

Deformities that – in contrast to diseases – are commonly irreversible may indicate sub-optimal rearing conditions (e.g., mechanical stress during hatching and rearing, environmental factors unless mentioned in crit. 3, aquatic pollutants, nutritional deficiencies) or a general incompatibility of the species with being farmed.

What is the probability of the species being malformed rarely?

It is low for minimal farming conditions, as malformation rates exceed 10%. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions, as some malformations result from conditions that may be changed. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

10 Slaughter

The cornerstone for a humane treatment is that slaughter a) immediately follows stunning (i.e., while the individual is unconscious), b) happens according to a clear and reproducible set of instructions verified under farming conditions, and c) avoids pain, suffering, and distress.

What is the probability of the species being slaughtered according to a humane slaughter protocol?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions, as innovations for stunning and slaughter need to be verified for the farming context. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

Side note: Domestication

Teletchea and Fontaine introduced 5 domestication levels illustrating how far species are from having their life cycle closed in captivity without wild input, how long they have been reared in captivity, and whether breeding programmes are in place.

What is the species’ domestication level?

DOMESTICATION LEVEL 5 84, fully domesticated.

Side note: Forage fish in the feed

450-1,000 milliard wild-caught fishes end up being processed into fish meal and fish oil each year which contributes to overfishing and represents enormous suffering. There is a broad range of feeding types within species reared in captivity.

To what degree may fish meal and fish oil based on forage fish be replaced by non-forage fishery components (e.g., poultry blood meal) or sustainable sources (e.g., soybean cake)?

All age classes:

- WILD: carnivorous 23.

- FARM: FRY: fish meal may be partly* replaced by sustainable sources 85. JUVENILES: fish meal may be completely* replaced by sustainable sources 86.

- LAB: JUVENILES: fish meal may be partly* 87 88 to mostly* 89 and fish oil may be mostly* replaced by sustainable sources 90.

*partly = <51% – mostly = 51-99% – completely = 100%

Side note: Commercial relevance

How much is this species farmed annually?

263,215 t/year 1990-2019 amounting to estimated 623,000,000-875,000,000 IND/year 1990-2019 91.

Glossary

AMPHIDROMOUS = migrating between fresh water and sea independent of spawning

DOMESTICATION LEVEL 5 = selective breeding programmes are used focusing on specific goals 84

EURYHALINE = tolerant of a wide range of salinities

FARM = setting in farming environment or under conditions simulating farming environment in terms of size of facility or number of individuals

FISHES = using "fishes" instead of "fish" for more than one individual - whether of the same species or not - is inspired by Jonathan Balcombe who proposed this usage in his book "What a fish knows". By referring to a group as "fishes", we acknowledge the individuals with their personalities and needs instead of an anonymous mass of "fish".

FRY = larvae from external feeding on

IND = individuals

JUVENILES = fully developed but immature individuals

LAB = setting in laboratory environment

LARVAE = hatching to mouth opening

PELAGIC = living independent of bottom and shore of a body of water

PHOTOPERIOD = duration of daylight

PLANKTONIC = horizontal movement limited to hydrodynamic displacement

SPAWNERS = adults during the spawning season; in farms: adults that are kept as broodstock

WILD = setting in the wild

Bibliography

2 Jennings, S., and M. G. Pawson. 1992. The origin and recruitment of bass, Dicentrarchus labrax, larvae to nursery areas. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 72: 199. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400048888.

3 Pickett, G.D, D.F Kelley, and M.G Pawson. 2004. The patterns of recruitment of sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax L. from nursery areas in England and Wales and implications for fisheries management. Fisheries Research 68: 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2003.11.013.

4 Hussenot, Jérôme M.E. 2003. Emerging effluent management strategies in marine fish-culture farms located in European coastal wetlands. Aquaculture 226: 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00472-1.

5 Özden, Osman, Şahin Saka, and Cüneyt Suzer. 2020. Current status of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) and European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) production in Turkey. In Marine aquaculture in Turkey: Advancements and management, ed. Deniz Çoban, M. Didem Demircan, and Deniz D. Tosun, 50–68. 59. Istanbul, Turkey: Turkish Marine Research Foundation.

6 Büke, Ergun. 2002. Sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L., 1781) seed production. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 2: 61–70.

7 Divanach, P., and M. Kentouri. 2000. Hatchery techniques for specific diversification in Mediterranean finfish larviculture. Cahiers options méditerranéennes 47: 75–87.

8 Holden, M. J., and T. Williams. 1974. The Biology, Movements and Population Dynamics of Bass, Dicentrarchus Labrax, in English Waters. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 54: 91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400022098.

9 Quayle, V.A., D. Righton, S. Hetherington, and G. Pickett. 2009. Observations of the Behaviour of European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in the North Sea. In Tagging and Tracking of Marine Animals with Electronic Devices, ed. Jennifer L. Nielsen, Haritz Arrizabalaga, Nuno Fragoso, Alistair Hobday, Molly Lutcavage, and John Sibert, 9:103–119. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

10 Arechavala-Lopez, P., I. Uglem, D. Fernandez-Jover, J. T. Bayle-Sempere, and P. Sanchez-Jerez. 2011. Immediate post-escape behaviour of farmed seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) in the Mediterranean Sea. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 27: 1375–1378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0426.2011.01786.x.

11 Green, Benjamin C., David J. Smith, Jonathan Grey, and Graham J. C. Underwood. 2012. High site fidelity and low site connectivity in temperate salt marsh fish populations: a stable isotope approach. Oecologia 168: 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-011-2077-y.

12 Bagni, M. 2005. Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme. Dicentrarchus labrax. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department.

13 Makridis, Pavlos, Elena Mente, Henrik Grundvig, Martin Gausen, Constantin Koutsikopoulos, and Asbjørn Bergheim. 2018. Monitoring of oxygen fluctuations in seabass cages (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) in a commercial fish farm in Greece. Aquaculture Research 49: 684–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.13498.

14 Nhhala, Hassan, Abdeljallil Bahida, Imane Nhhala, Housni Chadli, Azeddine Abrehouch, Benyounes Abdellaoui, Mohamed Id Halla, and Hassan Er-Raioui. 2022. Ecological risk analysis in marine fish farming: a case study of a seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) farm located in Moroccan Mediterranean coast. Edited by L. El Youssfi, A. Aghzar, S.I. Cherkaoui, A.G. Faundez, D.R. Salazar, E.S.P. Assèdé, O. Seidou, and Y. Ouaggajou. E3S Web of Conferences 337: 03003. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202233703003.

15 Maricchiolo, Giulia, Simone Mirto, Gabriella Caruso, Tiziana Caruso, Rosa Bonaventura, Monica Celi, Valeria Matranga, and Lucrezia Genovese. 2011. Welfare status of cage farmed European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax): A comparison between submerged and surface cages. Aquaculture 314: 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.02.001.

16 García García, Benjamín, Caridad Rosique Jiménez, Felipe Aguado-Giménez, and José García García. 2019. Life Cycle Assessment of Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) Produced in Offshore Fish Farms: Variability and Multiple Regression Analysis. Sustainability 11: 3523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133523.

17 Orduna, Carlos, Lourdes Encina, Amadora Rodríguez-Ruiz, and Victoria Rodríguez-Sánchez. 2021. Testing of new sampling methods and estimation of size structure of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in aquaculture farms using horizontal hydroacoustics. Aquaculture 545: 737242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737242.

18 Jerbi, M.A., J. Aubin, K. Garnaoui, L. Achour, and A. Kacem. 2012. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of two rearing techniques of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquacultural Engineering 46: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2011.10.001.

19 Saleem, Basma, Ola Orma, Amr Abd El-Wahab, and Tarek Ibrahim. 2022. Growth performance parameters of European Sea bass (Dicentrarchus Labrax) cultured in marine water farm and fed commercial diets of different protein levels. Mansoura Veterinary Medical Journal 23: 10–17. https://doi.org/10.21608/mvmj.2022.229849.

20 Pawson, M. G., G. D. Pickett, and D. F. Kelley. 1987. The distribution and migrations of bass, Dicentrarchus labrax L., in waters around England and Wales as shown by tagging. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 67: 183. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400026448.

21 Pawson, M. G., G. D. Pickett, J. Leballeur, M. Brown, and M. Fritsch. 2006. Migrations, fishery interactions, and management units of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in Northwest Europe. ICES Journal of Marine Science 64: 332–345. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsl035.

22 Moretti, Alessandro, Mario Pedini Fernandez-Criado, Giancarlo Cittolin, and Ruggero Guidastri. 1999. Manual on Hatchery Production of Seabass and Gilthead Seabream. Vol. 1. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

23 Pickett, Graham D, and Michael G Pawson. 1994. Sea Bass: Biology. Vol. 12. Springer Science & Business Media.

24 Mylonas, Constantinos C. 2017. Personal communicationEMail.

25 Bégout Anras, M-L, J-P Lagardére, and J-Y Lafaye. 1997. Diel activity rhythm of seabass tracked in a natural environment: group effects on swimming patterns and amplitudes. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 54: 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1139/f96-253.

26 Brehmer, Patrice, Thang Do Chi, and David Mouillot. 2006. Amphidromous fish school migration revealed by combining fixed sonar monitoring (horizontal beaming) with fishing data. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 334: 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2006.01.017.

27 Benhaïm, David, Samuel Péan, Gaël Lucas, Nancy Blanc, Béatrice Chatain, and Marie-Laure Bégout. 2012. Early life behavioural differences in wild caught and domesticated sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Applied Animal Behaviour Science 141: 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2012.07.002.

28 Karakassis, I. 2000. Impact of cage farming of fish on the seabed in three Mediterranean coastal areas. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57: 1462–1471. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsc.2000.0925.

29 MacPherson, N., G Citollin, H. Cook, and S. Besikepe. 1988. The farming of sea bass, sea bream and shrimp in Iskenderun Bay - An Assessment of Technical and Economic Feasibility.

30 Dando, P. R., and Necla Demir. 1985. On the Spawning and Nursery Grounds of Bass, Dicentrarchus Labrax, in the Plymouth Area. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 65: 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400060872.

31 Thompson, Brenda M., and Ruth T. Harrop. 1987. The distribution and abundance of bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) eggs and larvae in the English Channel and Southern North Sea. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 67: 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400026588.

32 Naciri, M. 1999. Genetic study of the Atlantic/Mediterranean transition in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Journal of Heredity 90: 591–596. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/90.6.591.

33 Martinho, F., R. Leitão, J. M. Neto, H. Cabral, F. Lagardère, and M. A. Pardal. 2008. Estuarine colonization, population structure and nursery functioning for 0-group sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), flounder (Platichthys flesus) and sole (Solea solea) in a mesotidal temperate estuary. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 24: 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0426.2007.01049.x.

34 Kennedy, Michael, and Patrick Fitzmaurice. 1972. The Biology of the Bass, Dicentrarchus Labrax, in Irish Waters. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 52: 557. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400021597.

35 Fahy, E., N. Forrest, U. Shaw, and P. Green. 2000. Observations on the status of bass Dicentrarchus Labrax stocks in Ireland in the late 1990s. Irish Fisheries Investigations 5.

36 Cabral, Henrique, and Maria José Costa. 2001. Abundance, feeding ecology and growth of 0-group sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax, within the nursery areas of the Tagus estuary. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 81: 679–682. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315401004362.

37 Kaplan, Murat, and Mehmet Taner Karaoğlu. 2021. Investigation of betanodavirus in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) at all production stages in all hatcheries and on selected farms in Turkey. Archives of Virology 166: 3343–3356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-021-05254-0.

38 Claridge, P. N., and I. C. Potter. 1983. Movements, abundance, age composition and growth of bass, Dicentrarchus labrax, in the Severn Estuary and inner Bristol Channel. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 63: 871–879. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400071289.

39 Kelley, D. F. 1988. The importance of estuaries for sea-bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.). Journal of Fish Biology 33: 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1988.tb05555.x.

40 Martinho, Filipe, R. Leitão, J. M. Neto, H. N. Cabral, J. C. Marques, and M. A. Pardal. 2007. The use of nursery areas by juvenile fish in a temperate estuary, Portugal. Hydrobiologia 587: 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-0689-3.

41 Pawson, M.G., and G.D. Pickett. 1996. The Annual Pattern of Condition and Maturity in Bass, Dicentrarchus Labrax, in Waters Around England and Wales. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 76: 107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400029040.

42 Vinagre, C., T. Ferreira, L. Matos, M. J. Costa, and H. N. Cabral. 2009. Latitudinal gradients in growth and spawning of sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax, and their relationship with temperature and photoperiod. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 81: 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2008.11.015.

43 Gorshkov, S., G. Gorshkova, and W. R. Knibb. 1999. Sex ratios and growth performance of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) reared in mariculture in Eilat (Red Sea). Israeli Journal of Aquaculture - Bamidgeh 51: 91–105.

44 Forniés, M.A, E Mañanós, M Carrillo, A Rocha, S Laureau, C.C Mylonas, Y Zohar, and S Zanuy. 2001. Spawning induction of individual European sea bass females (Dicentrarchus labrax) using different GnRHa-delivery systems. Aquaculture 202: 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00773-6.

45 Rainis, Simona, Constantinos C Mylonas, Yiannos Kyriakou, and Pascal Divanach. 2003. Enhancement of spermiation in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) at the end of the reproductive season using GnRHa implants. Aquaculture 219: 873–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00028-0.

46 Mylonas, Constantinos C., and Yonathan Zohar. 2000. Use of GnRHa-delivery systems for the control of reproduction in fish. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 10: 463–491. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012279814708.

47 Zanuy, Silvia, Manuel Carrillo, Alicia Felip, Lucinda Rodrı́guez, Mercedes Blázquez, Jesús Ramos, and Francesc Piferrer. 2001. Genetic, hormonal and environmental approaches for the control of reproduction in the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). Aquaculture 202: 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00771-2.

48 Zohar, Yonathan, and Constantinos C Mylonas. 2001. Endocrine manipulations of spawning in cultured fish: from hormones to genes. Aquaculture 197: 99–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00584-1.

49 Pavlidis, M., E. Karantzali, E. Fanouraki, C. Barsakis, S. Kollias, and N. Papandroulakis. 2011. Onset of the primary stress in European sea bass Dicentrarhus labrax, as indicated by whole body cortisol in relation to glucocorticoid receptor during early development. Aquaculture 315: 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.09.013.

50 Heath, M.R. 1992. Field Investigations of the Early Life Stages of Marine Fish. In Advances in Marine Biology, 28:1–174. Elsevier.

51 Hatziathanasiou, A., M. Paspatis, M. Houbart, P. Kestemont, S. Stefanakis, and M. Kentouri. 2002. Survival, growth and feeding in early life stages of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) intensively cultured under different stocking densities. Aquaculture 205: 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00672-X.

52 El-Sayed, Heba S., Mohamed A. Zaki, Abd El-Aziz M. Nour, Tamer A. A. Said, and Reham M. K. Negm. 2021. Effect of stocking density on survival rate, growth performance, swim bladder inflation and skeletal deformity of the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) larvae. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries 25: 979–994. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejabf.2021.184648.

53 Benhaïm, David, Marie-Laure Bégout, Gaël Lucas, and Béatrice Chatain. 2013. First Insight into Exploration and Cognition in Wild Caught and Domesticated Sea Bass ( Dicentrarchus labrax ) in a Maze. PLOS ONE 8: e65872. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065872.

54 Papoutsoglou, S, M J Costello, E Stamou, and G Tziha. 1996. Environmental conditions at sea-cages, and ectoparasites on farmed European sea-bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.), and gilt-head sea-bream, Sparus aurata L., at two farms in Greece. Aquaculture Research 27: 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.1996.tb00963.x.

55 Person-Le Ruyet, Jeannine, and Nicolas Le Bayon. 2009. Effects of temperature, stocking density and farming conditions on fin damage in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquatic Living Resources 22: 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1051/alr/2009047.

56 Di Marco, P., A. Priori, M.G. Finoia, A. Massari, A. Mandich, and G. Marino. 2008. Physiological responses of European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax to different stocking densities and acute stress challenge. Aquaculture 275: 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.12.012.

57 Lupatsch, I., G.A. Santos, J.W. Schrama, and J.A.J. Verreth. 2010. Effect of stocking density and feeding level on energy expenditure and stress responsiveness in European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. Aquaculture 298: 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.11.007.

58 Sammouth, Sophie, Emmanuelle Roque d’Orbcastel, Eric Gasset, Gilles Lemarié, Gilles Breuil, Giovanna Marino, Jean-Luc Coeurdacier, Sveinung Fivelstad, and Jean-Paul Blancheton. 2009. The effect of density on sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) performance in a tank-based recirculating system. Aquacultural Engineering 40: 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2008.11.004.

59 Giebichenstein, Jan, Julia Giebichenstein, Mario Hasler, Carsten Schulz, and Bernd Ueberschär. 2022. Comparing the performance of four commercial microdiets in an early weaning protocol for European seabass larvae (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquaculture Research 53: 544–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.15598.

60 Di-Poï, C., J. Attia, C. Bouchut, G. Dutto, D. Covès, and M. Beauchaud. 2007. Behavioral and neurophysiological responses of European sea bass groups reared under food constraint. Physiology & Behavior 90: 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.11.005.

61 Ferrari, Sébastien, Sandie Millot, Didier Leguay, Béatrice Chatain, and Marie-Laure Bégout. 2015. Consistency in European seabass coping styles: A life-history approach. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 167: 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2015.03.006.

62 Benhaïm, David, Samuel Péan, Blandine Brisset, Didier Leguay, Marie-Laure Bégout, and Béatrice Chatain. 2011. Effect of size grading on sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) juvenile self-feeding behaviour, social structure and culture performance. Aquatic Living Resources 24: 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1051/alr/2011140.

63 Jackman, L. A. J. 1954. The early development stages of the Bass, Morone labrax (L.). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 124: 531–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1954.tb07795.x.

64 Leis, Jeffrey M. 2006. Are Larvae of Demersal Fishes Plankton or Nekton? In Advances in Marine Biology, 51:57–141. Elsevier.

65 Millot, S., M.-L. Bégout, and B. Chatain. 2009. Risk-taking behaviour variation over time in sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax: effects of day–night alternation, fish phenotypic characteristics and selection for growth. Journal of Fish Biology 75: 1733–1749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02425.x.

66 Killen, Shaun S., Stefano Marras, and David J. McKenzie. 2011. Fuel, fasting, fear: routine metabolic rate and food deprivation exert synergistic effects on risk-taking in individual juvenile European sea bass. Journal of Animal Ecology 80: 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01844.x.

67 Ferrari, Sébastien, David Benhaïm, Tatiana Colchen, Béatrice Chatain, and Marie-Laure Bégout. 2014. First links between self-feeding behaviour and personality traits in European seabass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 161: 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2014.09.019.

68 Arechavala-Lopez, Pablo, Samira Nuñez-Velazquez, Carlos Diaz-Gil, Guillermo Follana-Berná, and João L. Saraiva. 2022. Suspended Structures Reduce Variability of Group Risk-Taking Responses of Dicentrarchus labrax Juvenile Reared in Tanks. Fishes 7: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes7030126.

69 Vazzana, M, M Cammarata, E.L Cooper, and N Parrinello. 2002. Confinement stress in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) depresses peritoneal leukocyte cytotoxicity. Aquaculture 210: 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00818-3.

70 Varsamos, S., G. Flik, J.F. Pepin, S.E. Wendelaar Bonga, and G. Breuil. 2006. Husbandry stress during early life stages affects the stress response and health status of juvenile sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 20: 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2005.04.005.

71 Fatira, E., N. Papandroulakis, and M. Pavlidis. 2013. Diel changes in plasma cortisol and effects of size and stress duration on the cortisol response in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Fish Physiology and Biochemistry 40: 911–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-013-9896-1.

72 Fanouraki, E., N. Papandroulakis, T. Ellis, C. C. Mylonas, A. P. Scott, and M. Pavlidis. 2008. Water cortisol is a reliable indicator of stress in European sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Behaviour 145: 1267–1281. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853908785765818.

73 Marino, G., C. Boglione, B. Bertolini, A. Rossi, F. Ferreri, and S. Cataudella. 1993. Observations on development and anomalies in the appendicular skeleton of sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax L. 1758, larvae and juveniles. Aquaculture Research 24: 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.1993.tb00568.x.

74 Barahona-Fernandes, M. H. 1982. Body deformation in hatchery reared European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax (L). Types, prevalence and effect on fish survival. Journal of Fish Biology 21: 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1982.tb02830.x.

75 Chatain, Beatrice. 1994. Abnormal swimbladder development and lordosis in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and sea bream (Sparus auratus). Aquaculture 119: 371–379. https://doi.org/0044-8486/94.

76 Koumoundouros, G, E Maingot, P Divanach, and M Kentouri. 2002. Kyphosis in reared sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.): ontogeny and effects on mortality. Aquaculture 209: 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00821-3.

77 Abdel, I., E. Abellán, O. López-Albors, P. Valdés, M.J. Nortes, and A. García-Alcázar. 2004. Abnormalities in the juvenile stage of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) reared at different temperatures: types, prevalence and effect on growth. Aquaculture International 12: 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-004-0349-9.

78 EFSA. 2009. Species-specific welfare aspects of the main systems of stunning and killing of farmed Seabass and Seabream. EFSA Journal 1010: 1–52. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1010.

79 Lines, J. A., and J. Spencer. 2012. Safeguarding the welfare of farmed fish at harvest. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry 38: 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-011-9561-5.

80 de la Rosa, Ignacio, Pedro L. Castro, and Rafael Ginés. 2021. Twenty Years of Research in Seabass and Seabream Welfare during Slaughter. Animals 11: 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082164.

81 Lambooij, Bert, Marien A Gerritzen, Henny Reimert, Dirk Burggraaf, Geert André, and Hans Van De Vis. 2008. Evaluation of electrical stunning of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in seawater and killing by chilling: welfare aspects, product quality and possibilities for implementation. Aquaculture Research 39: 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2007.01860.x.

82 Simitzis, Panagiotis E, Aristeidis Tsopelakos, Maria A Charismiadou, Alkisti Batzina, Stelios G Deligeorgis, and Helen Miliou. 2013. Comparison of the effects of six stunning/killing procedures on flesh quality of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax, Linnaeus 1758) and evaluation of clove oil anaesthesia followed by chilling on ice/water slurry for potential implementation in aquaculture. Aquaculture Research: n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.12120.

83 Zampacavallo, Giulia, Giuliana Parisi, Massimo Mecatti, Paola Lupi, Gianluca Giorgi, and Bianca Maria Poli. 2015. Evaluation of different methods of stunning/killing sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) by tissue stress/quality indicators. Journal of Food Science and Technology 52: 2585–2597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-014-1324-8.

84 Teletchea, Fabrice, and Pascal Fontaine. 2012. Levels of domestication in fish: implications for the sustainable future of aquaculture. Fish and Fisheries 15: 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12006.

85 Wassef, Elham, Shaban Abdel-Geid Abdel-Momen, Norhan E. Saleh, Ahmed M. Al-Zayat, and Ahmed M. Ashry. 2019. European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) performance, health status, immune response and intestinal morphology after feeding a mixture of plant proteins-containing diets. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries 23: 77–91. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejabf.2019.52408.

86 Hassan, Salama E., Ahmad M. Azab, Hamdy A. Abo-Taleb, and Mohamed M. El-Feky. 2020. Effect of replacing fish meal in the fish diet by zooplankton meal on growth performance of Dicentrarchus labrax (Linnaeus, 1758). Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries 24: 267–280. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejabf.2020.111756.

87 Oliva-Teles, Aires, and Paula Gonçalves. 2001. Partial replacement of fishmeal by brewers yeast (Saccaromyces cerevisae) in diets for sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) juveniles. Aquaculture 202: 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00777-3.

88 Torrecillas, Silvia, Daniel Montero, Marta Carvalho, Tibiabin Benitez-Santana, and Marisol Izquierdo. 2021. Replacement of fish meal by Antarctic krill meal in diets for European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax: Growth performance, feed utilization and liver lipid metabolism. Aquaculture 545: 737166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737166.

89 Kaushik, S.J., D. Covès, G. Dutto, and D. Blanc. 2004. Almost total replacement of fish meal by plant protein sources in the diet of a marine teleost, the European seabass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Aquaculture 230: 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00422-8.

90 Castro, C., G. Corraze, S. Panserat, and A. Oliva-Teles. 2015. Effects of fish oil replacement by a vegetable oil blend on digestibility, postprandial serum metabolite profile, lipid and glucose metabolism of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) juveniles. Aquaculture Nutrition 21: 592–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/anu.12184.

91 Mood, Alison, Elena Lara, Natasha K. Boyland, and Phil Brooke. 2023. Estimating global numbers of farmed fishes killed for food annually from 1990 to 2019. Animal Welfare 32: e12. https://doi.org/10.1017/awf.2023.4.

Lorem ipsum

Something along the lines of: we were aware of the importance of some topics so that we wanted to include them and collect data but not score them. For WelfareChecks | farm, these topics are "domestication level", "feed replacement", and "commercial relevance". The domestication and commercial relevance aspects allow us to analyse the questions whether increasing rate of domestication or relevance in farming worldwide goes hand in hand with better welfare; the feed replacement rather goes in the direction of added suffering for all those species which end up as feed. For a carnivorous species, to gain 1 kg of meat, you do not just kill this one individual but you have to take into account the meat that it was fed during its life in the form of fish meal and fish oil. In other words, carnivorous species (and to a degree also omnivorous ones) have a larger "fish in:fish out" ratio.

Lorem ipsum

Probably, we updated the profile. Check the version number in the head of the page. For more information on the version, see the FAQ about this. Why do we update profiles? Not just do we want to include new research that has come out, but we are continuously developing the database itself. For example, we changed the structure of entries in criteria or we added explanations for scores in the WelfareCheck | farm. And we are always refining our scoring rules.

The centre of the Overview is an array of criteria covering basic features and behaviours of the species. Each of this information comes from our literature search on the species. If we researched a full Dossier on the species, probably all criteria in the Overview will be covered and thus filled. This was our way to go when we first set up the database.

Because Dossiers are time consuming to research, we switched to focusing on WelfareChecks. These are much shorter profiles covering just 10 criteria we deemed important when it comes to behaviour and welfare in aquaculture (and lately fisheries, too). Also, WelfareChecks contain the assessment of the welfare potential of a species which has become the main feature of the fair-fish database over time. Because WelfareChecks do not cover as many criteria as a Dossier, we don't have the information to fill all blanks in the Overview, as this information is "not investigated by us yet".

Our long-term goal is to go back to researching Dossiers for all species covered in the fair-fish database once we set up WelfareChecks for each of them. If you would like to support us financially with this, please get in touch at ffdb@fair-fish.net

See the question "What does "not investigated by us yet" mean?". In short, if we have not had a look in the literature - or in other words, if we have not investigated a criterion - we cannot know the data. If we have already checked the literature on a criterion and could not find anything, it is "no data found yet". You spotted a "no data found yet" where you know data exists? Get in touch with us at ffdb@fair-fish.net!

Once you have clicked on "show details", the entry for a criterion will unfold and display the summarised information we collected from the scientific literature – complete with the reference(s).

As reference style we chose "Springer Humanities (numeric, brackets)" which presents itself in the database as a number in a grey box. Mouse over the box to see the reference; click on it to jump to the bibliography at the bottom of the page. But what does "[x]-[y]" refer to?

This is the way we mark secondary citations. In this case, we read reference "y", but not reference "x", and cite "x" as mentioned in "y". We try to avoid citing secondary references as best as possible and instead read the original source ourselves. Sometimes we have to resort to citing secondarily, though, when the original source is: a) very old or not (digitally) available for other reasons, b) in a language no one in the team understands. Seldomly, it also happens that we are running out of time on a profile and cannot afford to read the original. As mentioned, though, we try to avoid it, as citing mistakes may always happen (and we don't want to copy the mistake) and as misunderstandings may occur by interpreting the secondarily cited information incorrectly.

If you spot a secondary reference and would like to send us the original work, please contact us at ffdb@fair-fish.net

In general, we aim at giving a good representation of the literature published on the respective species and read as much as we can. We do have a time budget on each profile, though. This is around 80-100 hours for a WelfareCheck and around 300 hours for a Dossier. It might thus be that we simply did not come around to reading the paper.

It is also possible, though, that we did have to make a decision between several papers on the same topic. If there are too many papers on one issue than we manage to read in time, we have to select a sample. On certain topics that currently attract a lot of attention, it might be beneficial to opt for the more recent papers; on other topics, especially in basic research on behaviour in the wild, the older papers might be the go-to source.

And speaking of time: the paper you are missing from the profile might have come out after the profile was published. For the publication date, please check the head of the profile at "cite this profile". We currently update profiles every 6-7 years.

If your paper slipped through the cracks and you would like us to consider it, please get in touch at ffdb@fair-fish.net

This number, for example "C | 2.1 (2022-11-02)", contains 4 parts:

- "C" marks the appearance – the design level – of the profile part. In WelfareChecks | farm, appearance "C" is our most recent one with consistent age class and label (WILD, FARM, LAB) structure across all criteria.

- "2." marks the number of major releases within this appearance. Here, it is major release 2. Major releases include e.g. changes of the WelfareScore. Even if we just add one paper – if it changes the score for one or several criteria, we will mark this as a major update for the profile. With a change to a new appearance, the major release will be re-set to 1.

- ".1" marks the number of minor updates within this appearance. Here, it is minor update 1. With minor updates, we mean changes in formatting, grammar, orthography. It can also mean adding new papers, but if these papers only confirm the score and don't change it, it will be "minor" in our book. With a change to a new appearance, the minor update will be re-set to 0.

- "(2022-11-02)" is the date of the last change – be it the initial release of the part, a minor, or a major update. The nature of the changes you may find out in the changelog next to the version number.

If an Advice, for example, has an initial release date and then just a minor update date due to link corrections, it means that – apart from correcting links – the Advice has not been updated in a major way since its initial release. Please take this into account when consulting any part of the database.

First up, you will find answers to questions for the specific page you are on. Scrolling down in the FAQ window, there are also answers to more general questions. Explore our website and the other sub pages and find there the answers to questions relevant for those pages.

In the fair-fish database, when you have chosen a species (either by searching in the search bar or in the species tree), the landing page is an Overview, introducing the most important information to know about the species that we have come across during our literatures search, including common names, images, distribution, habitat and growth characteristics, swimming aspects, reproduction, social behaviour but also handling details. To dive deeper, visit the Dossier where we collect all available ethological findings (and more) on the most important aspects during the life course, both biologically and concerning the habitat. In contrast to the Overview, we present the findings in more detail citing the scientific references.

Depending on whether the species is farmed or wild caught, you will be interested in different branches of the database.

Farm branch

Founded in 2013, the farm branch of the fair-fish database focuses on farmed aquatic species.

Catch branch

Founded in 2022, the catch branch of the fair-fish database focuses on wild-caught aquatic species.

The heart of the farm branch of the fair-fish database is the welfare assessment – or WelfareCheck | farm – resulting in the WelfareScore | farm for each species. The WelfareCheck | farm is a condensed assessment of the species' likelihood and potential for good welfare in aquaculture, based on welfare-related findings for 10 crucial criteria (home range, depth range, migration, reproduction, aggregation, aggression, substrate, stress, malformations, slaughter).

For those species with a Dossier, we conclude to-be-preferred farming conditions in the Advice | farm. They are not meant to be as detailed as a rearing manual but instead, challenge current farming standards and often take the form of what not to do.

In parallel to farm, the main element of the catch branch of the fair-fish database is the welfare assessment – or WelfareCheck | catch – with the WelfareScore | catch for each species caught with a specific catching method. The WelfareCheck | catch, too, is a condensed assessment of the species' likelihood and potential for good welfare – or better yet avoidance of decrease of good welfare – this time in fisheries. We base this on findings on welfare hazards in 10 steps along the catching process (prospection, setting, catching, emersion, release from gear, bycatch avoidance, sorting, discarding, storing, slaughter).

In contrast to the farm profiles, in the catch branch we assess the welfare separately for each method that the focus species is caught with. In the case of a species exclusively caught with one method, there will be one WelfareCheck, whereas in other species, there will be as many WelfareChecks as there are methods to catch the species with.

Summarising our findings of all WelfareChecks | catch for one species in Advice | catch, we conclude which catching method is the least welfare threatening for this species and which changes to the gear or the catching process will potentially result in improvements of welfare.

Welfare of aquatic species is at the heart of the fair-fish database. In our definition of welfare, we follow Broom (1986): “The welfare of an individual is its state as regards its attempts to cope with its environment.” Thus, welfare may be perceived as a continuum on which an individual rates “good” or “poor” or everything in between.

We pursue what could be called a combination of not only a) valuing the freedom from injuries and stress (function-based approach) but b) supporting attempts to provide rewarding experiences and cognitive challenges (feelings-based approach) as well as c) arguing for enclosures that mimic the wild habitat as best as possible and allow for natural behaviour (nature-based approach).

Try mousing over the element you are interested in - oftentimes you will find explanations this way. If not, there will be FAQ on many of the sub-pages with answers to questions that apply to the respective sub-page. If your question is not among those, contact us at ffdb@fair-fish.net.

It's right here! We decided to re-name it to fair-fish database for several reasons. The database has grown beyond dealing purely with ethology, more towards welfare in general – and so much more. Also, the partners fair-fish and FishEthoGroup decided to re-organise their partnership. While maintaining our friendship, we also desire for greater independence. So, the name "fair-fish database" establishes it as a fair-fish endeavour.