Information

Author: Caroline Marques Maia

Version: B | 1.2Published: 2024-12-31

- minor editorial changes plus new side note "Commercial relevance"

WelfareScore | farm

The score card gives our welfare assessments for aquatic species in 10 criteria.

For each criterion, we score the probability to experience good welfare under minimal farming conditions ("Likelihood") and under high-standard farming conditions ("Potential") representing the worst and best case scenario. The third dimension scores how certain we are of our assessments based on the number and quality of sources we found ("Certainty").

The WelfareScore sums just the "High" scores in each dimension. Although good welfare ("High") seems not possible in some criteria, there could be at least a potential improvement from low to medium welfare (indicated by ➚ and the number of criteria).

- Li = Likelihood that the individuals of the species experience good welfare under minimal farming conditions

- Po = Potential of the individuals of the species to experience good welfare under high-standard farming conditions

➚ = potential improvements not reaching "High" - Ce = Certainty of our findings in Likelihood and Potential

WelfareScore = Sum of criteria scoring "High" (max. 10 per dimension)

General remarks

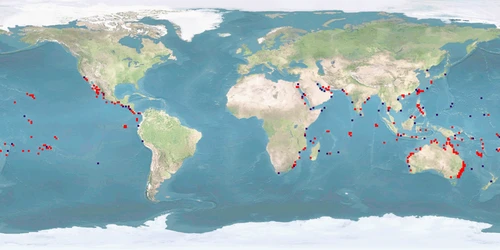

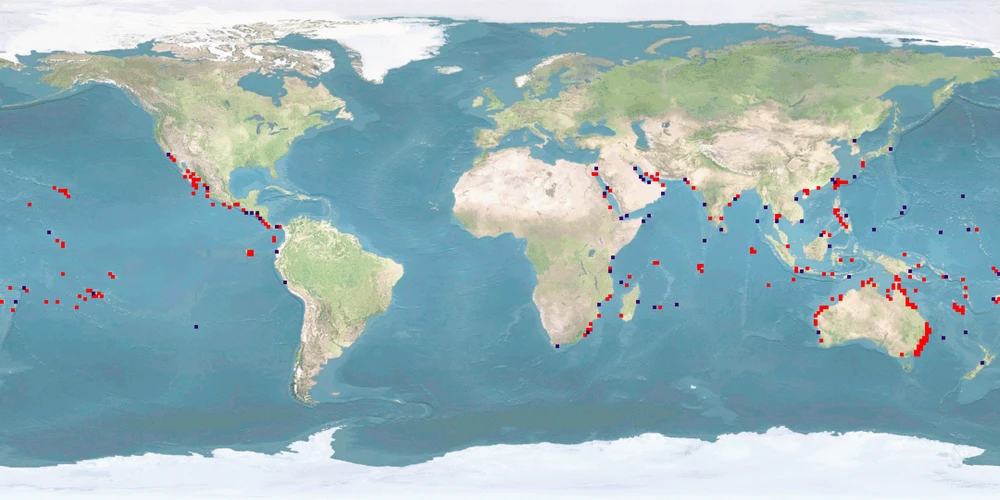

Chanos chanos is a BENTHOPELAGIC Indo-Pacific fish species that is found along continental shelves and around islands of low latitude tropics or in the subtropical northern hemisphere where temperatures are higher than 20 °C. This euryhaline fish can be found in fresh, brackish, and marine waters, occurring in small to large schools near the coasts or around islands where reefs are well developed. It is an AMPHIDROMOUS species: SPAWNERS release eggs in oceanic waters, then older LARVAE migrate onshore and settle in coastal wetlands like mangroves or estuaries (occasionally entering freshwater lakes), and JUVENILES then migrate back to sea where they mature sexually.

C. chanos is especially valued as a food fish in Southeast Asia and also used in game fish as bait. Taiwan, Indonesia, and Philippines – countries that started to culture this fish about 4-6 centuries ago – are the main producers. This fish is tolerant to low concentrations of oxygen and is usually farmed in ponds, pens, or cages in wide salinity ranges. Although being able to spawn naturally in captivity, the traditional farming usually depended on an annual restocking of ponds with FINGERLINGS reared from wild-caught FRY. Now farms are obtaining FRY from hatcheries. C. chanos is harvested and marketed mostly fresh or chilled, whole or deboned, frozen or processed. When harvested, individuals are JUVENILES. Thus, farming information about ADULTS are usually restricted to broodstock. Moreover, further studies about home range, aggression, substrate availability in farms, and stunning and slaughtering protocols are still needed for this species.

1 Home range

Many species traverse in a limited horizontal space (even if just for a certain period of time per year); the home range may be described as a species' understanding of its environment (i.e., its cognitive map) for the most important resources it needs access to.

What is the probability of providing the species' whole home range in captivity?

It is unclear for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

2 Depth range

Given the availability of resources (food, shelter) or the need to avoid predators, species spend their time within a certain depth range.

What is the probability of providing the species' whole depth range in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

3 Migration

Some species undergo seasonal changes of environments for different purposes (feeding, spawning, etc.), and to move there, they migrate for more or less extensive distances.

What is the probability of providing farming conditions that are compatible with the migrating or habitat-changing behaviour of the species?

It is low for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

4 Reproduction

A species reproduces at a certain age, season, and sex ratio and possibly involving courtship rituals.

What is the probability of the species reproducing naturally in captivity without manipulation of these circumstances?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is high for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

5 Aggregation

Species differ in the way they co-exist with conspecifics or other species from being solitary to aggregating unstructured, casually roaming in shoals or closely coordinating in schools of varying densities.

What is the probability of providing farming conditions that are compatible with the aggregation behaviour of the species?

It is unclear for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

6 Aggression

There is a range of adverse reactions in species, spanning from being relatively indifferent towards others to defending valuable resources (e.g., food, territory, mates) to actively attacking opponents.

What is the probability of the species being non-aggressive and non-territorial in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a low amount of evidence.

7 Substrate

Depending on where in the water column the species lives, it differs in interacting with or relying on various substrates for feeding or covering purposes (e.g., plants, rocks and stones, sand and mud, turbidity).

What is the probability of providing the species' substrate and shelter needs in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is high for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

8 Stress

Farming involves subjecting the species to diverse procedures (e.g., handling, air exposure, short-term confinement, short-term crowding, transport), sudden parameter changes or repeated disturbances (e.g., husbandry, size-grading).

What is the probability of the species not being stressed?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a high amount of evidence.

9 Malformations

Deformities that – in contrast to diseases – are commonly irreversible may indicate sub-optimal rearing conditions (e.g., mechanical stress during hatching and rearing, environmental factors unless mentioned in crit. 3, aquatic pollutants, nutritional deficiencies) or a general incompatibility of the species with being farmed.

What is the probability of the species being malformed rarely?

It is low for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

10 Slaughter

The cornerstone for a humane treatment is that slaughter a) immediately follows stunning (i.e., while the individual is unconscious), b) happens according to a clear and reproducible set of instructions verified under farming conditions, and c) avoids pain, suffering, and distress.

What is the probability of the species being slaughtered according to a humane slaughter protocol?

There are no findings for minimal and high-standard farming conditions.

Side note: Domestication

Teletchea and Fontaine introduced 5 domestication levels illustrating how far species are from having their life cycle closed in captivity without wild input, how long they have been reared in captivity, and whether breeding programmes are in place.

What is the species’ domestication level?

DOMESTICATION LEVEL 4 41, level 5 being fully domesticated.

Side note: Forage fish in the feed

450-1,000 milliard wild-caught fishes end up being processed into fish meal and fish oil each year which contributes to overfishing and represents enormous suffering. There is a broad range of feeding types within species reared in captivity.

To what degree may fish meal and fish oil based on forage fish be replaced by non-forage fishery components (e.g., poultry blood meal) or sustainable sources (e.g., soybean cake)?

WILD: omnivorous 24 29 25 1 42, mainly feeding on blue-green algae 11, but FRY and JUVENILES also on detritus and plant materials 2 and FRY on plankton 24 11 1. FARM: fertilised ponds with no supplementary feeding is possible 24 14 15 33, but supplemental feeding (e.g., rice bran or copra meal) is used for better growth 24 14. Fish meal may not be replaced in FRY 9, but may be completely* replaced by sustainable resources for JUVENILES 17. LAB: FRY: fish meal may be not 38 to partly* 43 44 replaced by sustainable or non-forage fishery sources; fish oil may be partly* 44 to completely* replaced by sustainable sources, with better growth and survival when mostly* replaced 40. JUVENILES: fish meal may be partly* replaced by sustainable sources 42.

partly = <51% – mostly = 51-99% – completely = 100%

Side note: Commercial relevance

How much is this species farmed annually?

1,327,153 t/year 1990-2019 amounting to estimated 3,620,000,000-6,148,000,000 IND/year 1990-2019 45.

Glossary

AMPHIDROMOUS = migrating between fresh water and sea independent of spawning

BENTHIC = living at the bottom of a body of water, able to rest on the floor

BENTHOPELAGIC = living and feeding near the bottom of a body of water, floating above the floor

DOMESTICATION LEVEL 4 = entire life cycle closed in captivity without wild inputs 41

EURYHALINE = tolerant of a wide range of salinities

FARM = setting in farming environment or under conditions simulating farming environment in terms of size of facility or number of individuals

FINGERLINGS = early juveniles with fully developed scales and working fins, the size of a human finger

FRY = larvae from external feeding on

IND = individuals

JUVENILES = fully developed but immature individuals

LAB = setting in laboratory environment

LARVAE = hatching to mouth opening

PELAGIC = living independent of bottom and shore of a body of water

PHOTOPERIOD = duration of daylight

PLANKTONIC = horizontal movement limited to hydrodynamic displacement

SPAWNERS = adults during the spawning season; in farms: adults that are kept as broodstock

WILD = setting in the wild

Bibliography

2 Kumagai, S., T. Bagarinao, and A. Unggui. 1985. Growth of juvenile milkfish Chanos chanos in a natural habitat. Marine Ecology Progress Series 22: 1–6.

3 Lalramchhani, C., C. P. Balasubramanian, A. Panigrahi, T. K. Ghoshal, S. Das, P. S. S. Anand, and K. K. Vijayan. 2019. Polyculture of Indian White Shrimp (Penaeus indicus) with Milkfish (Chanos chanos) and its Effect on Growth Performances, Water Quality and Microbial Load in Brackishwater Pond. Journal of Coastal Research 86: 43–48. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI86-006.1.

4 Prijono, A., Tridjoko, I. N. A. Giri, A. Poernomo, W. E. Vanstone, C. Lim, and T. Daulay. 1988. Natural spawning and larval rearing of milkfish in captivity in Indonesia. Aquaculture 74: 127–130.

5 Emata, A. C., and C. L. Marte. 1994. Natural spawning, egg and fry production of milkfish, Chanos chanos (Forsskal), broodstock reared in concrete tanks1. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 10: 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0426.1994.tb00139.x.

6 Juario, J. V., M. N. Duray, V. M. Duray, J. F. Nacario, and J. M. E. Almendras. 1984. Induced breeding and larval rearing experiments with milkfish Chanos chanos (Forskal) in the Philippines. Aquaculture 36: 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(84)90054-1.

7 Marte, C. L., and F. J. Lacanilao. 1986. Spontaneous maturation and spawning of milkfish in floating net cages. Aquaculture 53: 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(86)90281-4.

8 Baliao, D. D., E. M. Rodriguez, and D. D. Gerochi. 1980. Growth and survival rates of hatchery-produced and wild milkfish fry grown to fingerling size in earthen nursery ponds. SEAFDEC Aquaculture Department Quarterly Research Report 4: 11–14.

9 Santiago, Corazon B., Julia B. Pantastico, Susana F. Baldia, and Ofelia S. Reyes. 1989. Milkfish (Chanos chanos) fingerling production in freshwater ponds with the use of natural and artificial feeds. Aquaculture 77: 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(89)90215-9.

10 Hilomen-Garcia, G. V. 1997. Morphological abnormalities in hatchery-bred milkfish (Chanos chanos Forsskal) fry and juveniles. Aquaculture 152: 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(96)01518-9.

11 Cruz, E. M., and I. L. Laudencia. 1980. Polyculture of milkfish (Chanos chanos Forskal), all-male Nile tilapia (Tilapia nilotica) and snakehead (Ophicephalus striatus) in freshwater ponds with supplemental feeding. Aquaculture 20: 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(80)90113-1.

12 Pinto, L. 1982. Growth of Chanos chanos Forskal and Tilapia mossambica in a fish pond-saltern complex in Las Pinas, The Philippines. Aquaculture 29: 169–170.

13 Sumagaysay-Chavoso, N. S., and M. L. San Diego-McGlone. 2003. Water quality and holding capacity of intensive and semi-intensive milkfish (Chanos chanos) ponds. Aquaculture 219: 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00576-8.

14 Biswas, G., J. K. Sundaray, A. R. Thirunavukkarasu, and M. Kailasam. 2011. Length-weight relationship and variation in condition of Chanos chanos (Forsskål, 1775) from tide-fed brackishwater ponds of the Sunderbans - India. Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Science 40: 386–390.

15 Mirera, D. O. 2011. Experimental Polyculture of Milkfish (Chanos chanos) and Mullet (Mugil cephalus) Using Earthen Ponds. Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science 10: 59–71. https://doi.org/10.4314/WIOJMS.V10I1.

16 Hanke, I., C. Hassenrück, B. Ampe, A. Kunzmann, A. Gärdes, and J. Aerts. 2020. Chronic stress under commercial aquaculture conditions: Scale cortisol to identify and quantify potential stressors in milkfish (Chanos chanos) mariculture. Aquaculture 526: 735352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735352.

17 Go, M. B., S. P. Velos, G. P. Bate, and A. S. Ilano. 2018. Growth Performance of Milkfish (Chanos chanos) Fed Plant-Based Diets. Journal of Academic Research 3: 18–29.

18 Emata, A. C. 2000. Live Transport of Pond‐reared Milkfish Chanos chanos Broodstock. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 31: 279–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-7345.2000.tb00364.x.

19 Marte, C. L., N. M. Sherwood, L. W. Crim, and B. Harvey. 1987. Induced spawning of maturing milkfish (Chanos chanos Forsskal) with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues administered in various ways. Aquaculture 60: 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(87)90295-X.

20 Marte, C. L., N. Sherwood, L. Crim, and J. Tan. 1988. Induced spawning of maturing milkfish (Chanos chanos) using human chorionic gonadotropin and mammalian and salmon gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues. Aquaculture 73: 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(88)90066-X.

21 Garcia, L. M. B., G. V. Hilomen-Garcia, and A. C. Emata. 2000. Survival of captive milkfish Chanos chanos Forsskal broodstock subjected to handling and transport. Aquaculture Research 31: 575–583. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2109.2000.00475.x.

22 Lee, C.-S., C. S. Tamaru, C. D. Kelley, and J. E. Banno. 1986. Induced spawning of milkfish, Chanos chanos, by a single application of LHRH-analogue. Aquaculture 58: 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(86)90158-4.

23 Toledo, J. D., and A. G. Gaitan. 1992. Egg cannibalism by milkfish (Chanos chanos Forsskal) spawners in circular floating net cages. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 8: 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0426.1992.tb00692.x.

24 Froese, R., and D. Pauly. 2022. Chanos chanos, Milkfish: fisheries, aquaculture, aquarium. World Wide Web electronic publication. FishBase. https://www.fishbase.se/summary/citation.php. Accessed January 13.

25 Bagarinao, T. U. 1991. Biology of milkfish (Chanos chanos Forsskal). Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines: Aquaculturc Department Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC).

26 Bagarinao, T., and S. Kumagai. 1987. Occurrence and distribution of milkfish larvae,Chanos chanos off the western coast of Panay Island, Philippines. Environmental Biology of Fishes 19: 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00001886.

27 Shao, K. T., and P. L. Lim. 1991. Fishes of freshwater and estuary. Encyclopedia of field guide in Taiwan. Vol. 31. Taipei, Taiwan: Recreation Press, Co., Ltd.,.

28 Bacchet, P., T. Zysman, and Y. Lefèvre. 2006. Guide des poissons de Tahiti et ses îles. Tahiti (Polynésie Francaise): Éditions Au Vent des Îles.

29 Bagarinao, T., and K. Thayaparan. 1986. The length-weight relationship, food habits and condition factor of wild juvenile milkfish in Sri Lanka. Aquaculture 55: 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(86)90119-5.

30 Martosudarmo, B., S. Noor-Hamid, and S. Sabaruddin. 1976. Occurrence of milkfish, Chanos chanos (Forsskal), spawners in the Karimun Jawa waters. Bull. Shrimp Cult. Res. Centre Jepara 2: 169–176.

31 Riede, K. 2004. Global register of migratory species - from global to regional scales. Final report of the R&D Projekt 808 05 081. Bonn, Germany: Federal Agency for Nature Conservation.

32 Shadrack, R. S., S. Gereva, T. Pickering, and M. Ferreira. 2021. Seasonality, abundance and spawning season of milkfish Chanos chanos (Forsskål, 1775) at Teouma Bay, Vanuatu. Marine Policy 130: 104587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104587.

33 A’yun, Q., and N. D. Takarina. 2019. Food preference analysis of milkfish in Blanakan Ponds, Subang, West Java. AIP Conference Proceedings 2168: 020083. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5132510.

34 Kanashiro, K., and S. Asato. 1985. Mature Milkfish, Chanos chanos, Caught in Okinawa Island, Japan. Japanese Journal of Ichthyology 31: 434–437. https://doi.org/10.11369/jji1950.31.434.

35 Kuo, C.-M., and C. E. Nash. 1979. Annual reproductive cycle of milkfish, Chanos chanos Forskal, in Hawaiian waters. Aquaculture 16: 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(79)90113-3.

36 Rabanal, H. R., R. S. Esguerra, and M. M. Nepomuceno. 1953. Studies on the rate of growth of milkfish, Chanos chanos Forsskal, under cultivation. I. Rate of growth of fry and fingerlings in fishpond nurseries. Proc. Indo-Pac. Fish. Coun. 4: 171–180.

37 Villegas, C. T., and I. Bombeo. 1981. Effects of increased stocking density and supplemental feeding on the production of milkfish fingerlings. SEAFDEC Aquaculture Dept. Quart. Res. Rep. 5: 7–ll.

38 Seneriches, M. L. M., and Y. N. Chiu. 1988. Effect of fishmeal on the growth, survival and feed efficiency of milkfish (Chanos chanos) fry. Aquaculture 71: 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(88)90273-6.

39 Bhaskar, B., and K. S. Srinivasa. 1989. Influence of environmental variables on haematology, and compendium of normal haematological ranges of milkfish, Chanos chanos (Forskal), in brackishwater culture. Aquaculture 83: 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(89)90066-5.

40 Sivaramakrishnan, T., K. Ambasankar, K. P. K. Vasagam, J. S. Dayal, K. P. Sandeep, A. Bera, M. Makesh, M. Kailasam, and K. K. Vijayan. 2021. Effect of dietary soy lecithin inclusion levels on growth, feed utilization, fatty acid profile, deformity and survival of milkfish (Chanos chanos) larvae. Aquaculture Research 52: 5366–5374. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.15406.

41 Teletchea, Fabrice, and Pascal Fontaine. 2012. Levels of domestication in fish: implications for the sustainable future of aquaculture. Fish and Fisheries 15: 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12006.

42 Bharathi, S., C. Antony, C. B. T. Rajagopalsamy, A. Uma, B. Ahilan, R. S. S. Lingam, S. F. Khan, and E. Prabu. 2020. Partial replacement of fishmeal with soybean meal and distillers dried grain solubles (DDGS) as alternative protein sources for milkfish, Chanos chanos (Forsskal, 1775) fingerlings. Indian Journal of Fisheries 67: 62–70. https://doi.org/10.21077/ijf.2020.67.4.99940-08.

43 Santiago, C. B., M. Bañes-Aldaba, and E. T. Songalia. 1983. Effect of artificial diets on growth and survival of milkfish fry in fresh water. Aquaculture 34: 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(83)90206-5.

44 Alava, V. R., and C. Lim. 1988. Artificial diets for milkfish, Chanos chanos (Forsskal), fry reared in seawater. Aquaculture 71: 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(88)90203-7.

45 Mood, Alison, Elena Lara, Natasha K. Boyland, and Phil Brooke. 2023. Estimating global numbers of farmed fishes killed for food annually from 1990 to 2019. Animal Welfare 32: e12. https://doi.org/10.1017/awf.2023.4.

Lorem ipsum

Something along the lines of: we were aware of the importance of some topics so that we wanted to include them and collect data but not score them. For WelfareChecks | farm, these topics are "domestication level", "feed replacement", and "commercial relevance". The domestication and commercial relevance aspects allow us to analyse the questions whether increasing rate of domestication or relevance in farming worldwide goes hand in hand with better welfare; the feed replacement rather goes in the direction of added suffering for all those species which end up as feed. For a carnivorous species, to gain 1 kg of meat, you do not just kill this one individual but you have to take into account the meat that it was fed during its life in the form of fish meal and fish oil. In other words, carnivorous species (and to a degree also omnivorous ones) have a larger "fish in:fish out" ratio.

Lorem ipsum

Probably, we updated the profile. Check the version number in the head of the page. For more information on the version, see the FAQ about this. Why do we update profiles? Not just do we want to include new research that has come out, but we are continuously developing the database itself. For example, we changed the structure of entries in criteria or we added explanations for scores in the WelfareCheck | farm. And we are always refining our scoring rules.

The centre of the Overview is an array of criteria covering basic features and behaviours of the species. Each of this information comes from our literature search on the species. If we researched a full Dossier on the species, probably all criteria in the Overview will be covered and thus filled. This was our way to go when we first set up the database.

Because Dossiers are time consuming to research, we switched to focusing on WelfareChecks. These are much shorter profiles covering just 10 criteria we deemed important when it comes to behaviour and welfare in aquaculture (and lately fisheries, too). Also, WelfareChecks contain the assessment of the welfare potential of a species which has become the main feature of the fair-fish database over time. Because WelfareChecks do not cover as many criteria as a Dossier, we don't have the information to fill all blanks in the Overview, as this information is "not investigated by us yet".

Our long-term goal is to go back to researching Dossiers for all species covered in the fair-fish database once we set up WelfareChecks for each of them. If you would like to support us financially with this, please get in touch at ffdb@fair-fish.net

See the question "What does "not investigated by us yet" mean?". In short, if we have not had a look in the literature - or in other words, if we have not investigated a criterion - we cannot know the data. If we have already checked the literature on a criterion and could not find anything, it is "no data found yet". You spotted a "no data found yet" where you know data exists? Get in touch with us at ffdb@fair-fish.net!

Once you have clicked on "show details", the entry for a criterion will unfold and display the summarised information we collected from the scientific literature – complete with the reference(s).

As reference style we chose "Springer Humanities (numeric, brackets)" which presents itself in the database as a number in a grey box. Mouse over the box to see the reference; click on it to jump to the bibliography at the bottom of the page. But what does "[x]-[y]" refer to?

This is the way we mark secondary citations. In this case, we read reference "y", but not reference "x", and cite "x" as mentioned in "y". We try to avoid citing secondary references as best as possible and instead read the original source ourselves. Sometimes we have to resort to citing secondarily, though, when the original source is: a) very old or not (digitally) available for other reasons, b) in a language no one in the team understands. Seldomly, it also happens that we are running out of time on a profile and cannot afford to read the original. As mentioned, though, we try to avoid it, as citing mistakes may always happen (and we don't want to copy the mistake) and as misunderstandings may occur by interpreting the secondarily cited information incorrectly.

If you spot a secondary reference and would like to send us the original work, please contact us at ffdb@fair-fish.net

In general, we aim at giving a good representation of the literature published on the respective species and read as much as we can. We do have a time budget on each profile, though. This is around 80-100 hours for a WelfareCheck and around 300 hours for a Dossier. It might thus be that we simply did not come around to reading the paper.

It is also possible, though, that we did have to make a decision between several papers on the same topic. If there are too many papers on one issue than we manage to read in time, we have to select a sample. On certain topics that currently attract a lot of attention, it might be beneficial to opt for the more recent papers; on other topics, especially in basic research on behaviour in the wild, the older papers might be the go-to source.

And speaking of time: the paper you are missing from the profile might have come out after the profile was published. For the publication date, please check the head of the profile at "cite this profile". We currently update profiles every 6-7 years.

If your paper slipped through the cracks and you would like us to consider it, please get in touch at ffdb@fair-fish.net

This number, for example "C | 2.1 (2022-11-02)", contains 4 parts:

- "C" marks the appearance – the design level – of the profile part. In WelfareChecks | farm, appearance "C" is our most recent one with consistent age class and label (WILD, FARM, LAB) structure across all criteria.

- "2." marks the number of major releases within this appearance. Here, it is major release 2. Major releases include e.g. changes of the WelfareScore. Even if we just add one paper – if it changes the score for one or several criteria, we will mark this as a major update for the profile. With a change to a new appearance, the major release will be re-set to 1.

- ".1" marks the number of minor updates within this appearance. Here, it is minor update 1. With minor updates, we mean changes in formatting, grammar, orthography. It can also mean adding new papers, but if these papers only confirm the score and don't change it, it will be "minor" in our book. With a change to a new appearance, the minor update will be re-set to 0.

- "(2022-11-02)" is the date of the last change – be it the initial release of the part, a minor, or a major update. The nature of the changes you may find out in the changelog next to the version number.

If an Advice, for example, has an initial release date and then just a minor update date due to link corrections, it means that – apart from correcting links – the Advice has not been updated in a major way since its initial release. Please take this into account when consulting any part of the database.

Lorem ipsum

In the fair-fish database, when you have chosen a species (either by searching in the search bar or in the species tree), the landing page is an Overview, introducing the most important information to know about the species that we have come across during our literatures search, including common names, images, distribution, habitat and growth characteristics, swimming aspects, reproduction, social behaviour but also handling details. To dive deeper, visit the Dossier where we collect all available ethological findings (and more) on the most important aspects during the life course, both biologically and concerning the habitat. In contrast to the Overview, we present the findings in more detail citing the scientific references.

Depending on whether the species is farmed or wild caught, you will be interested in different branches of the database.

Farm branch

Founded in 2013, the farm branch of the fair-fish database focuses on farmed aquatic species.

Catch branch

Founded in 2022, the catch branch of the fair-fish database focuses on wild-caught aquatic species.

The heart of the farm branch of the fair-fish database is the welfare assessment – or WelfareCheck | farm – resulting in the WelfareScore | farm for each species. The WelfareCheck | farm is a condensed assessment of the species' likelihood and potential for good welfare in aquaculture, based on welfare-related findings for 10 crucial criteria (home range, depth range, migration, reproduction, aggregation, aggression, substrate, stress, malformations, slaughter).

For those species with a Dossier, we conclude to-be-preferred farming conditions in the Advice | farm. They are not meant to be as detailed as a rearing manual but instead, challenge current farming standards and often take the form of what not to do.

In parallel to farm, the main element of the catch branch of the fair-fish database is the welfare assessment – or WelfareCheck | catch – with the WelfareScore | catch for each species caught with a specific catching method. The WelfareCheck | catch, too, is a condensed assessment of the species' likelihood and potential for good welfare – or better yet avoidance of decrease of good welfare – this time in fisheries. We base this on findings on welfare hazards in 10 steps along the catching process (prospection, setting, catching, emersion, release from gear, bycatch avoidance, sorting, discarding, storing, slaughter).

In contrast to the farm profiles, in the catch branch we assess the welfare separately for each method that the focus species is caught with. In the case of a species exclusively caught with one method, there will be one WelfareCheck, whereas in other species, there will be as many WelfareChecks as there are methods to catch the species with.

Summarising our findings of all WelfareChecks | catch for one species in Advice | catch, we conclude which catching method is the least welfare threatening for this species and which changes to the gear or the catching process will potentially result in improvements of welfare.

Try mousing over the element you are interested in - oftentimes you will find explanations this way. If not, there will be FAQ on many of the sub-pages with answers to questions that apply to the respective sub-page. If your question is not among those, contact us at ffdb@fair-fish.net.

It's right here! We decided to re-name it to fair-fish database for several reasons. The database has grown beyond dealing purely with ethology, more towards welfare in general – and so much more. Also, the partners fair-fish and FishEthoGroup decided to re-organise their partnership. While maintaining our friendship, we also desire for greater independence. So, the name "fair-fish database" establishes it as a fair-fish endeavour.